Guest Speaker: Kristina Wilson, Author

Hosted by: Docomomo NY Tri-State

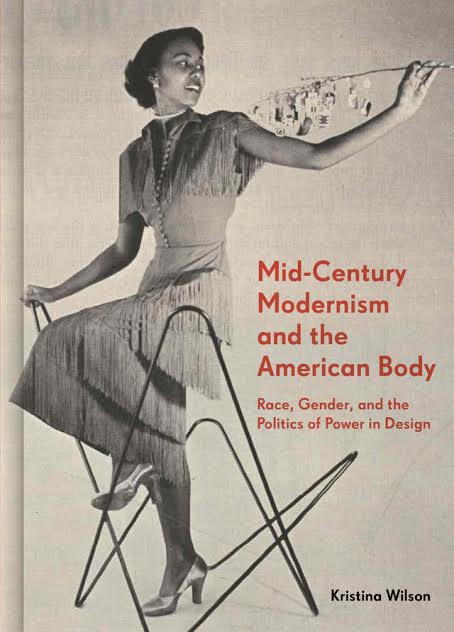

Kristina Wilson is a design historian and professor of art history at Clark University. She is the author of The Modern Eye and Livable Modernism. Her latest book, Mid-Century Modernism and the American Body: Race, Gender, and the Politics of Power in Design, was released on April 13, 2021. The book examines how race and gender shaped both the marketing + presentation of Modernist decor in postwar America.

Click here to read the full story ↓

The main focus of the talk centered around the reception of modern design— and how it circulated through the modern arenas of publications Life + Ebony. (These magazines were selected as reference materials because they spoke to the same types of people of different races). I attended the lecture and included a summary of the talk below.

Modern design started to gain popularity in the post war period. During this timeframe, segregation abounded and the civil rights + womens movements were taking place. Race and gender influenced Modern design and shaped the way it was presented to consumers.

Modern designs were connected to women. Wilson illustrates how etiquette and home decorating manuals served to control women by associating them with the domestic space.

The Mid-century years kept white women in view, but in their place. Designers exerted ‘control’ over women through their designs. In ads, women’s bodies were used as a prop to sell furniture.

The ideals defined by popular Modernist furnishings were far from neutral or race-blind. Through her research, Kristina found that Race & Modernism intersected in surprising ways. Control and exclusion were common themes made to reinforce whiteness and enforce segregation.

Advertisements from this time were fundamentally dissimilar in their approach as to how different races were portrayed. Black models were depicted as welcoming and “comfortable” in ads and editorials, while white models were shown as aloof, stiff and structured.

Modernism was an extreme agent of control and exclusion. The clean lines of modernism reinforced the vision of a clean home. The coded language signified a form of racial exclusion and segregation in modern homes and in the suburbs.

Ads from this era suggest modernism exemplifies high standards of cleanliness which must be “protected.” These ads, placed in periodicals with a white audience, become a signifier of exclusion. The ads convey a guarded feeling of white women trying to keep others out.

In contrast— in the pages of Ebony, Modernism appears as a prop of black social confidence. Ebony presented black readers with an image of Modernism as a style of comfort, security, and social confidence. In one ad, a husband sits on the couch, not the wife. There is a certain “pride of ownership” that exists. The women of color seem to invite us in.

To get a clearer picture of how this played out, review the comparative images presented in the book. The images highlight the inferences and ongoing disparity.

To me, this was one of the most interesting themes of the lecture. A comparative article featuring two successful designers:

An Ebony article showcasing Ad Bates, who is black— appeared after Life wrote about Charles Eames, who is white. While both articles were similar in structure & pacing, the approach couldn’t have been more fundamentally different.

Bates was a black furniture designer who created custom-built designs in East Harlem. In the Ebony layout, we see photos of Bates in his studio, working on a hand-crafted piece of furniture. We see the work space & table, with Bates working alongside his brother.

The physicality of his work is depicted in the images, and underscore the theme of agency of the black body. Bates demonstrates that he controls his own labor. The photos connote artistic freedom, collaboration and shared labor.

It is important to note that Bates originally wanted to be an upholsterer, but was barred from joining his chosen career path due to racism in the industry.

Charles Eames was a white furniture designer who created mass-produced designs, manufactured by Herman Miller in Zeeland, Michigan.

The Life spread emphasizes the finished product. Even in his portrait, Eames is dressed up and formal. All skill is hidden from view. He becomes a part of the design of the house. Ray appears in some domestic photos, but not in the portrait or elsewhere as a designer.

The biggest difference between how the two designers are depicted is exemplified in the professional landscape each artist is in.

Bates is an operator of a business, and knows precisely how much it brings in. He stresses that his relationship with his clients is of great importance. Bates relies heavily on custom design and he shows clients how the expense is worth it. He strives to suit their needs.

Eames has a team and isn’t a businessman. In the Life article, the Eames' designs exemplifies economy, and a stark + functional beauty. His furniture is mass-produced. The premise of the article is about the broad affordability of these furnishings.

In a Q&A session held after the lecture, the author briefly touched upon was the subject of the men behind these ads.

All publishers needed ad revenue to produce their magazine, regardless of color. Ebony interfaced with advertisers, and began expanding their reach to companies that usually catered to white households.

This began a push for corporations to market their products to not only white consumers, but to the black market as well. This prompted advertisers to begin marketing campaigns toward black readership. Black ad men became liaison with the corps.

If we review the situation that is currently playing out in the advertising realm— between black owners and corporations, I have to wonder how difficult (or seemingly impossible) this was to navigate at the time.

Black business owners of today-- in 2021, are speaking out about the lack of advertising spending with black-owned media companies.

Last week, Sean Combs penned a scathing letter in response to General Motors advertising expenditure with black enterprises. As evidenced by his assertion, we can deduce that the black experience with advertisers may not have progressed as much as we thought.